Domino Chain Effect

Using a 3D reconstruction system based on computer vision to record and analyze the mechanics of toppling domino blocks.

Highlights

- Built a stereo 3D reconstruction pipeline for capturing domino full dynamics

- Quantified 6 DOF chain reaction mechanics with color marker based tracking

- Presented poster at Women+ in Physics Canada 2025 (poster available in the bottom of the page.)

Introduction

The domino chain effect serves as a a prototypical marginally stable system, where a sufficient force applied to a single element in the chain initiates the the successive toppling of the dominoes.

Simplified models, like massless rods, single elastic/inelastic collisions, and relative sliding have been proposed and discussed, however, experimental validation remains limited. This study refines the use of high-speed video and computer vision techniques to analyze the domino effect.

Initial 2D analysis revealed multi-collision effects and enabled examination of the domino wave's acceleration stage before reaching a plateau of propagation speed. However, this method failed to capture out-of-plane block rotations, shown by Youtuber Smarter Every Day below, which exhibit a periodic influence on propagation speed, highlighting an overlooked aspect of the chain's dynamics.

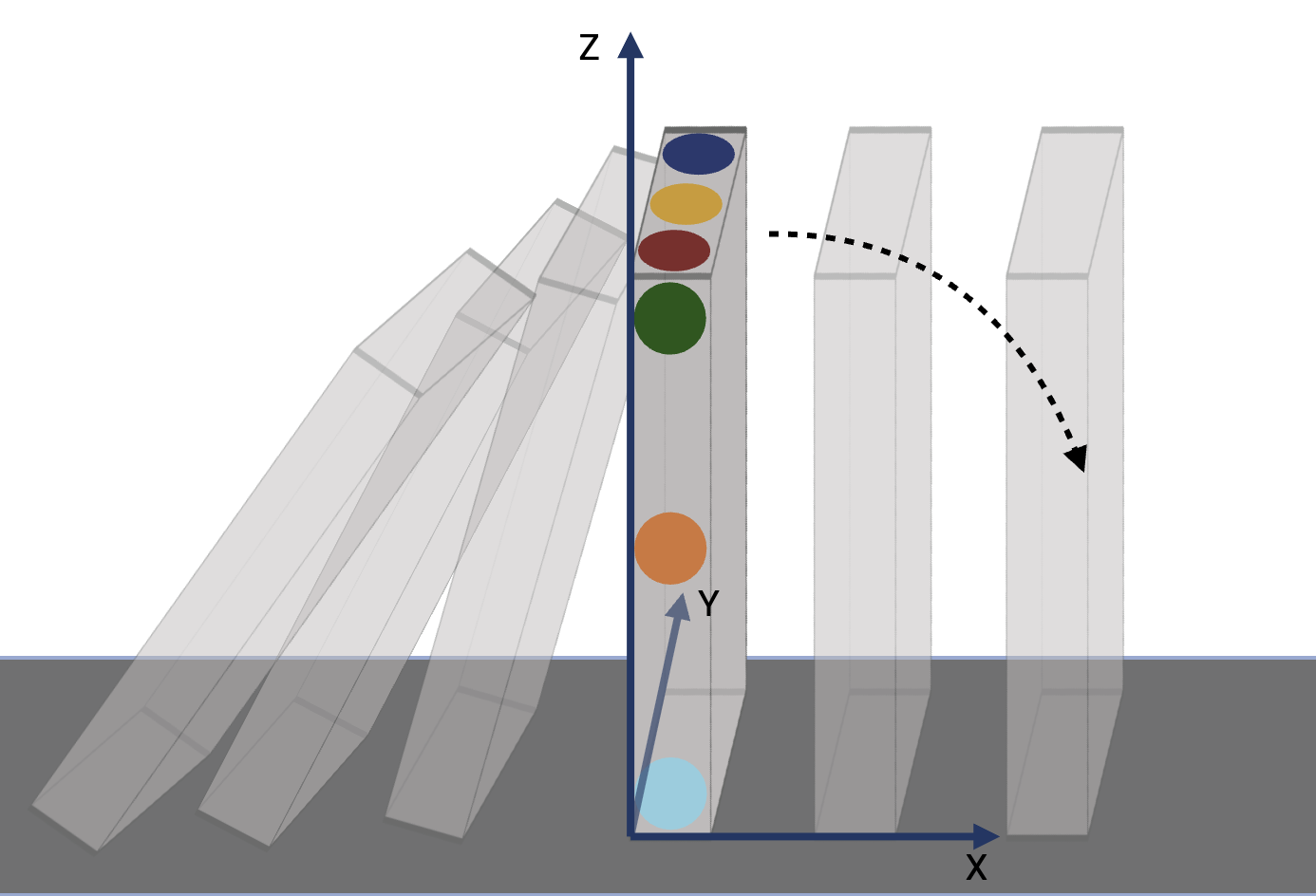

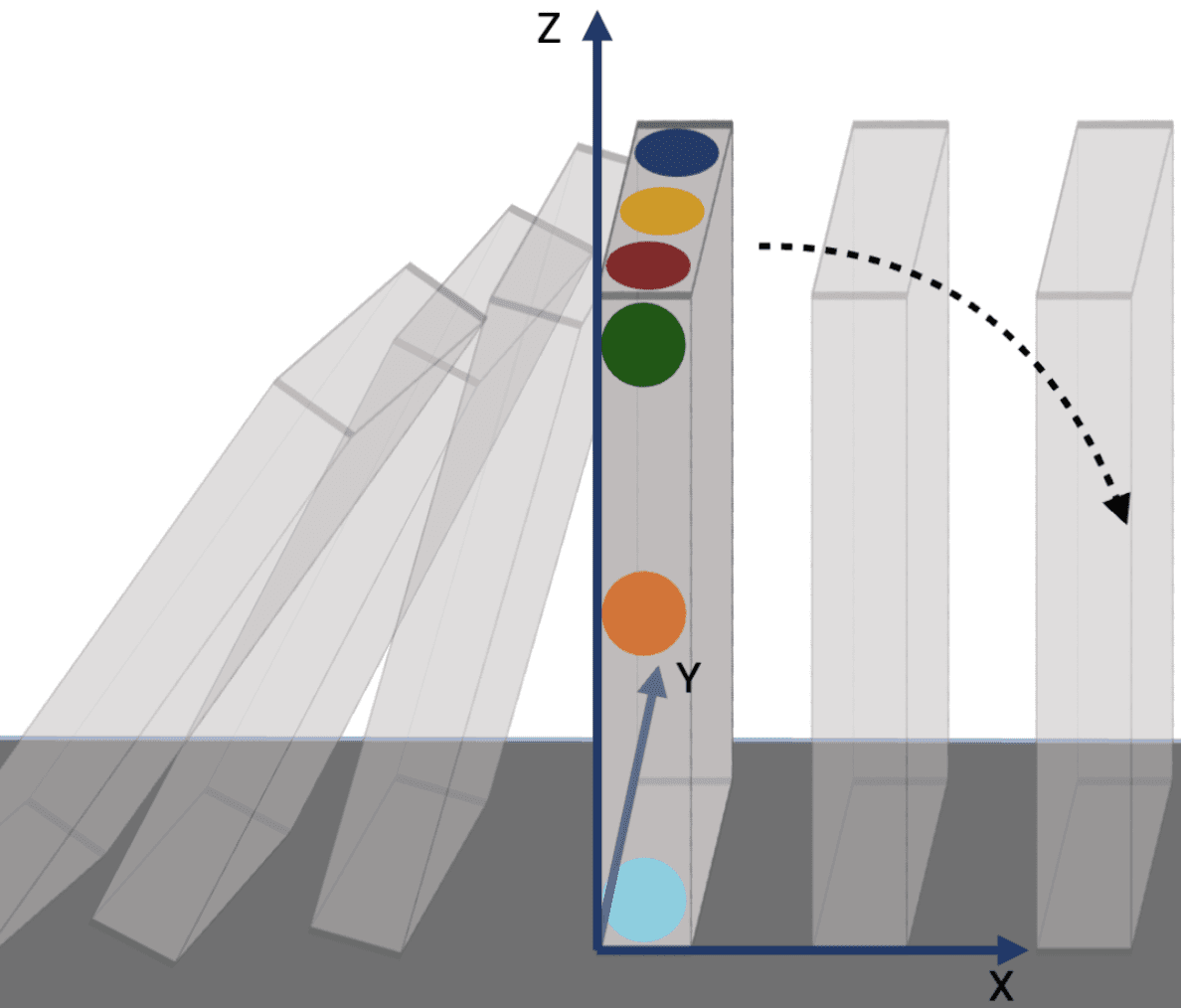

A 3D reconstruction system was then developed, enabling the full six degrees of freedom for each domino block within the chain reaction to be captured and analyzed.

2D Approach

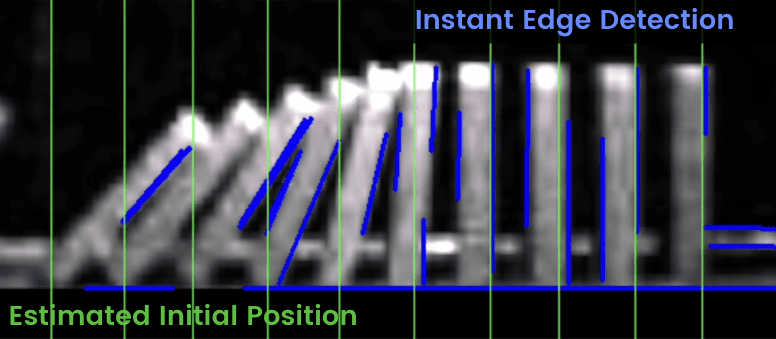

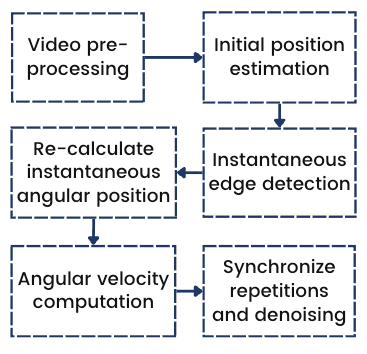

Following the workflow outlined in Figure 2, the initial positions obtained from edge detection (Figure 1) were used to reconstruct the domino toppling motion in 2D.

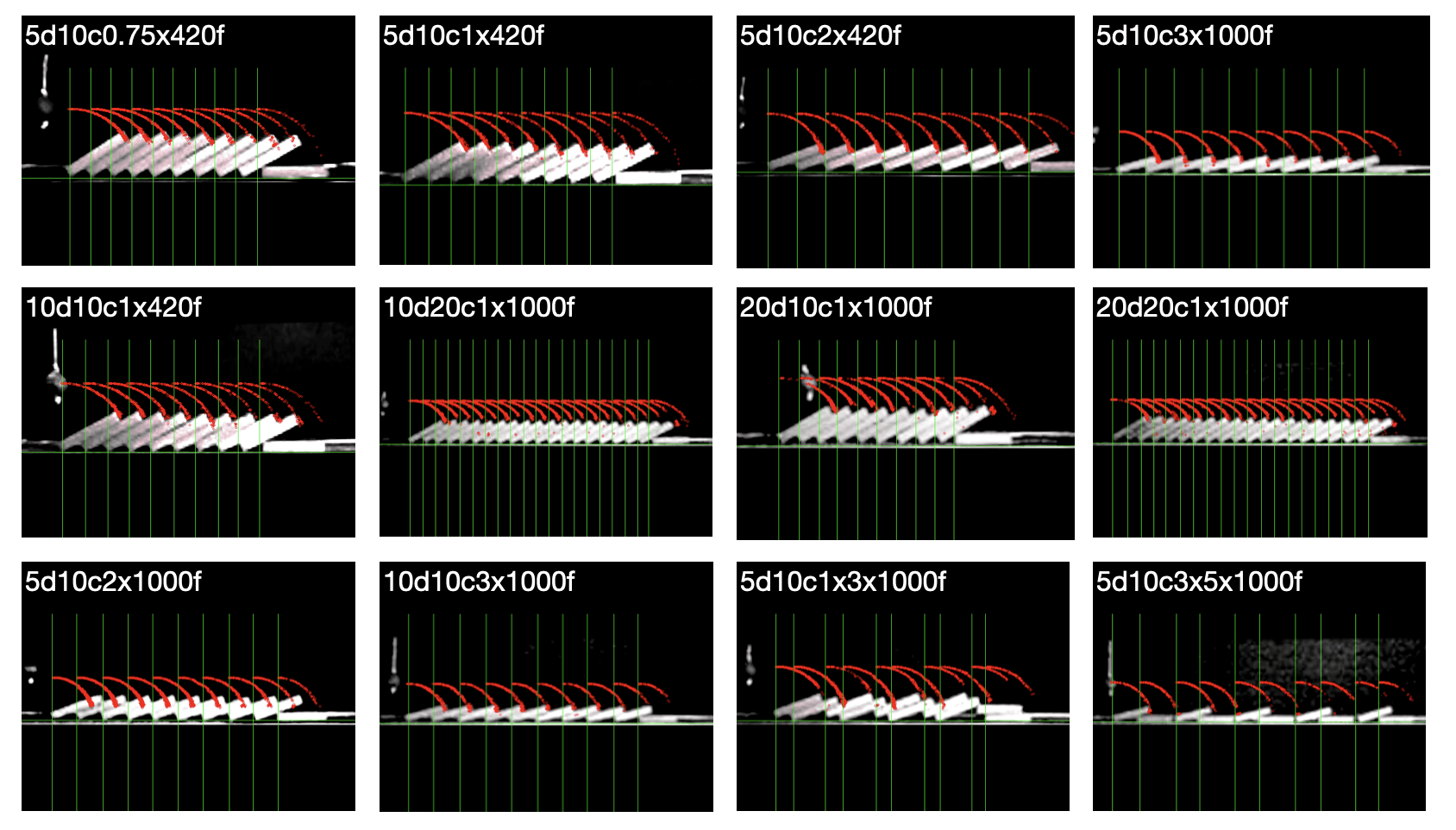

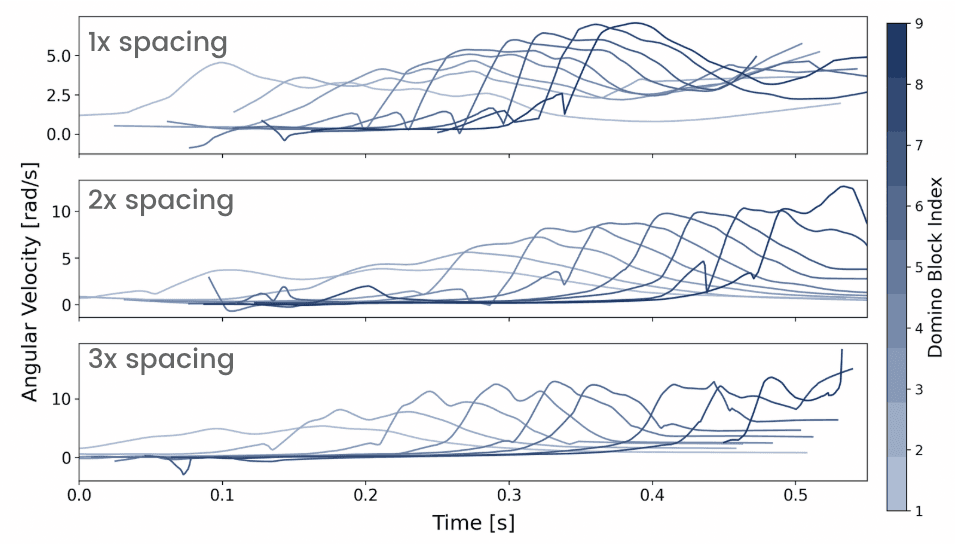

Examples of different setups with calculated reference points are shown in Figure 3 (detailed calculation steps are available in the project's GitHub repository), and the corresponding angular velocities extracted from the domino chain are presented in Figure 4.

We observe differences in the velocity curves (Figure 4) when varying domino spacing (e.g., *3 indicates spacing equal to three block widths). However, these velocities represent only the initial toppling phase and do not capture the system once domino transmission reaches a stable stage.

The 2D reconstruction pipeline relies on several simplifying assumptions: it assumes no relative sliding, fixes each block's lower-right edge, and ignores both off-plane rotations and near-edge camera distortion. The field of view also limits tracking to roughly 20 dominoes, restricting the scale of analysis. These assumptions deviate from real-world dynamics, where sliding and rotations are present. To address these limitations, a 3D extraction framework has been introduced.

3D Approach

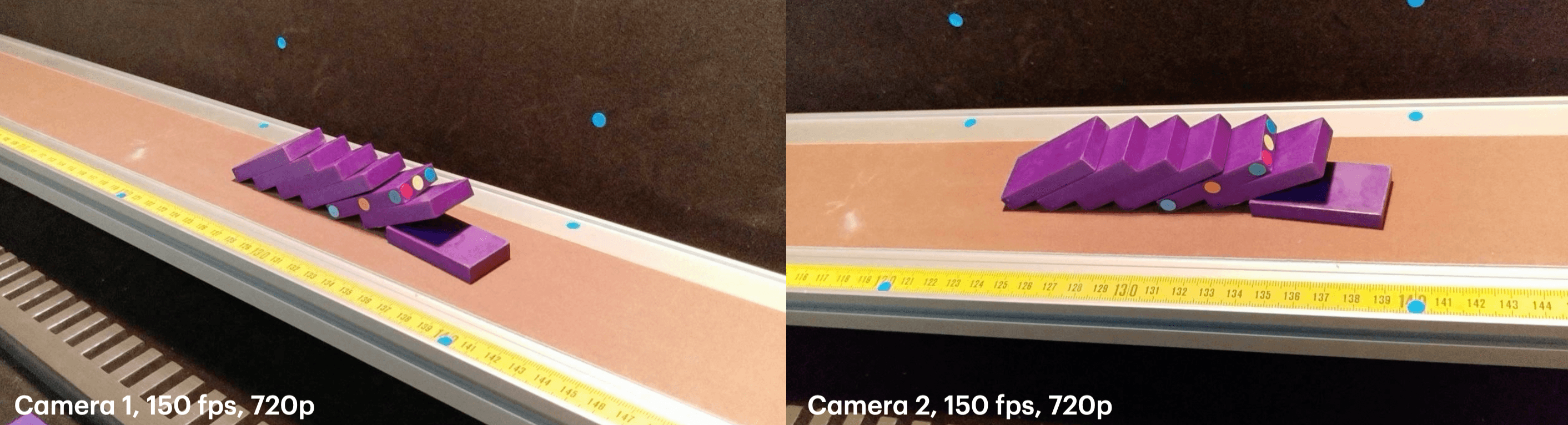

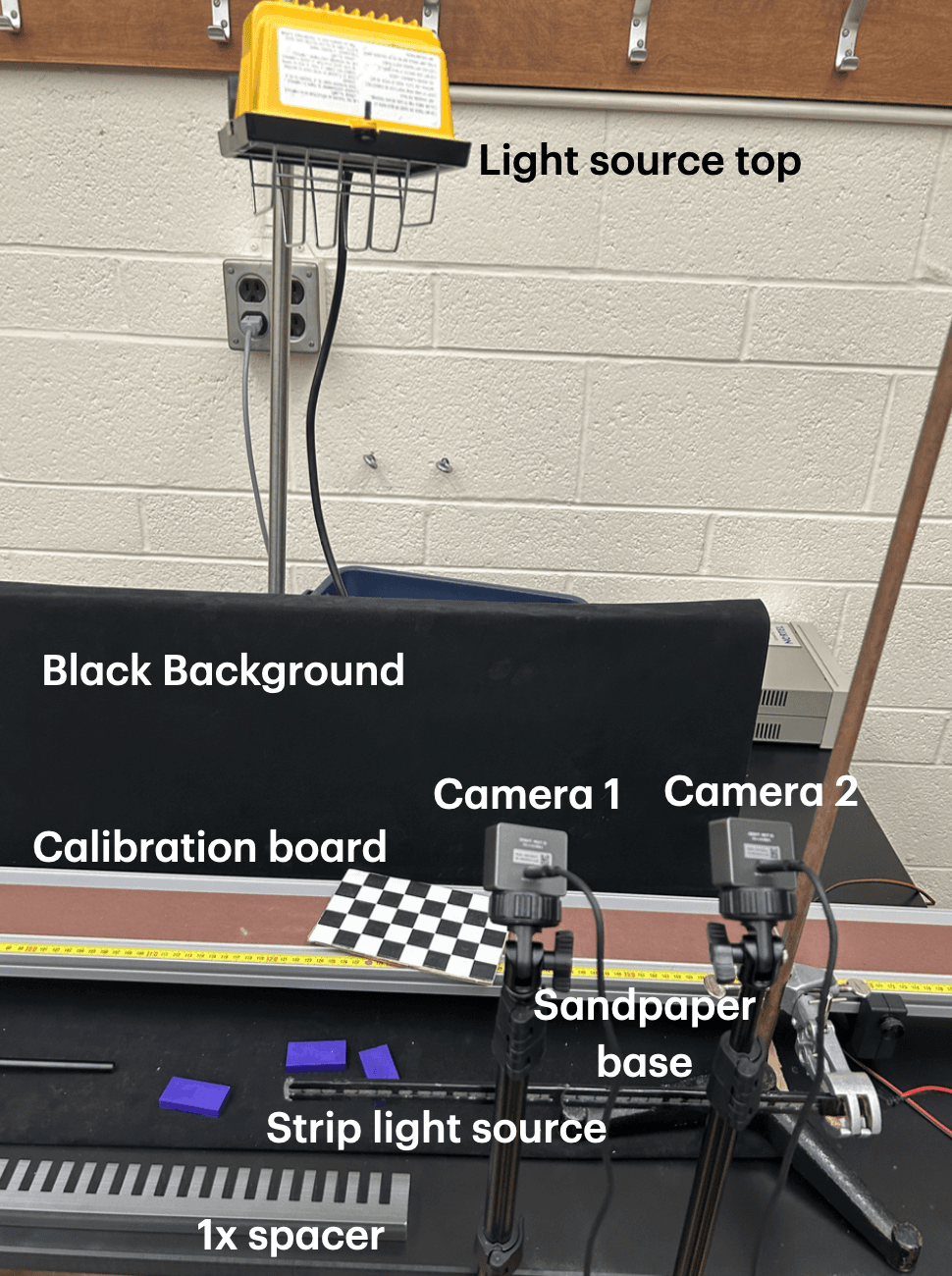

The 3D reconstruction setup consists of two cameras positioned at different viewpoints (Figure 5), a calibration board for alignment, and controlled lighting conditions, as shown in Figure 6.

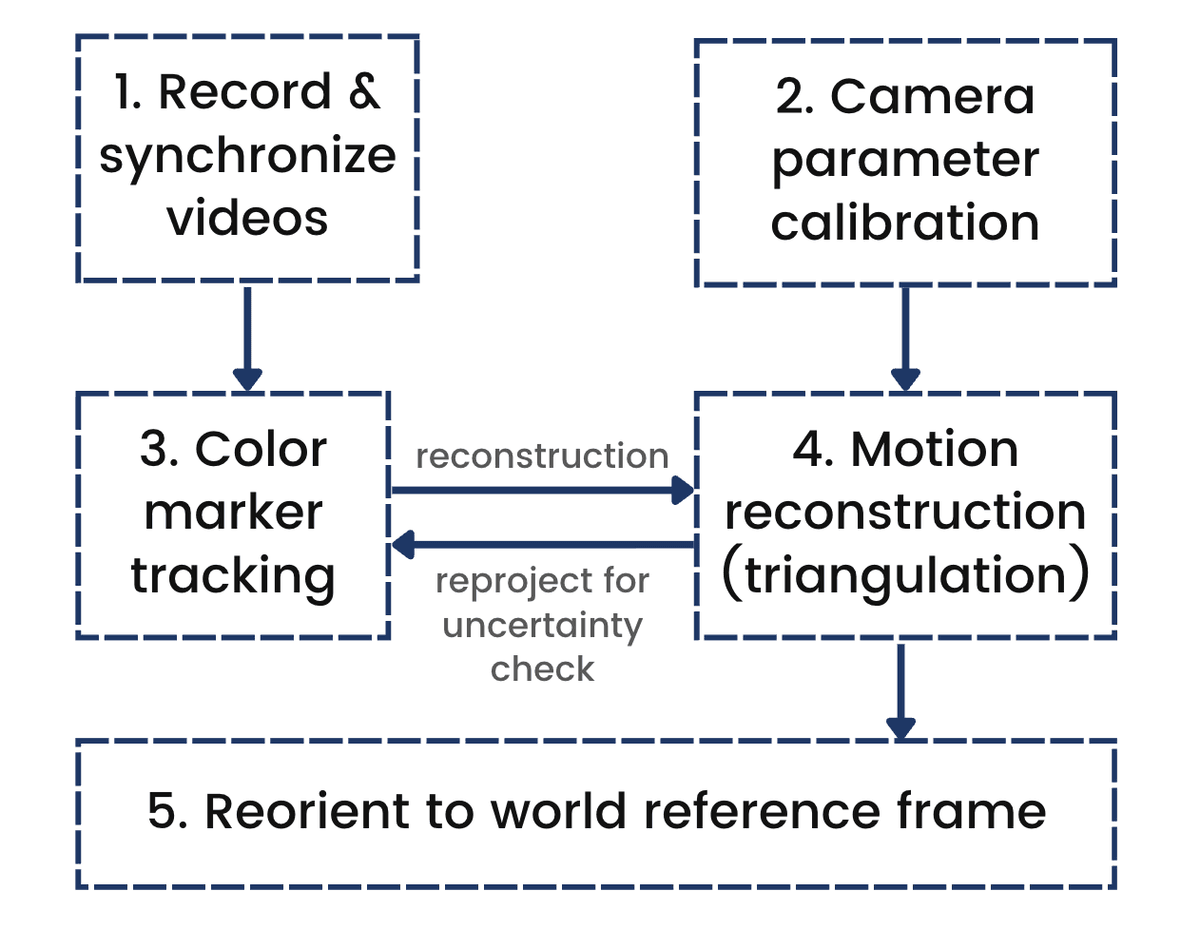

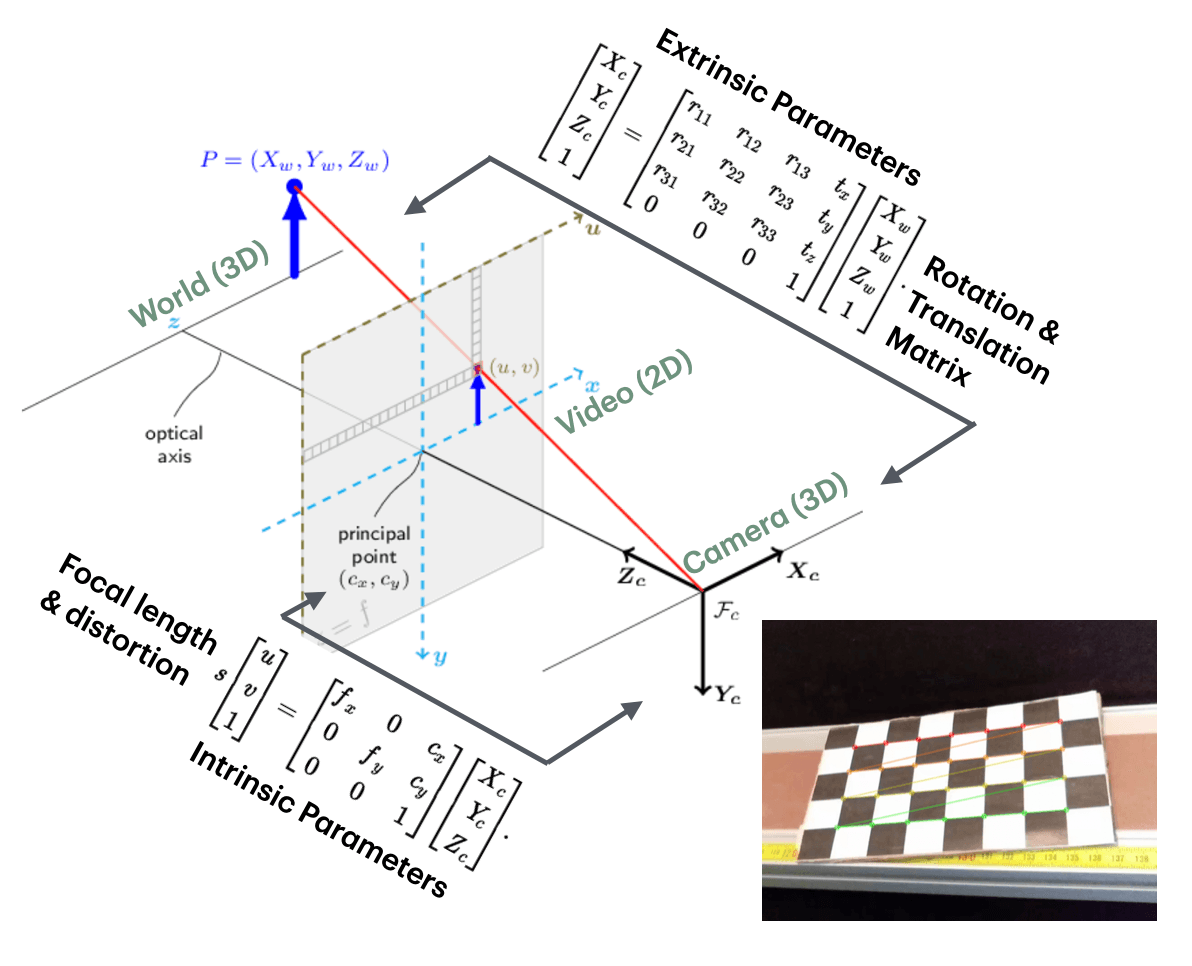

Following the reconstruction pipeline described in Figure 7, and with careful camera calibration using a checkerboard (Figure 8) along with color markers (Figure 9), we extracted and reconstructed the 3D trajectories of six markers, shown below.

The reconstruction error averages around ±3[mm]. However, systematic errors in color marker tracking remain difficult to verify. To address this, we are setting up a global reference anchor system (similar to those used in 3D printing).

While the designed pipeline theoretically captures full degrees of freedom, it still shows depth estimation uncertainty. As seen in the 3D model, marker trajectories are consistently over-slanted, suggesting a depth bias. This likely results from the use of only six co-planar markers, as well as imprecise calibration and world anchor frame setup. To address this, we plan to introduce front-facing markers to improve depth referencing and establish a more robust reference frame system.

6 Degree-of-Freedom Motion

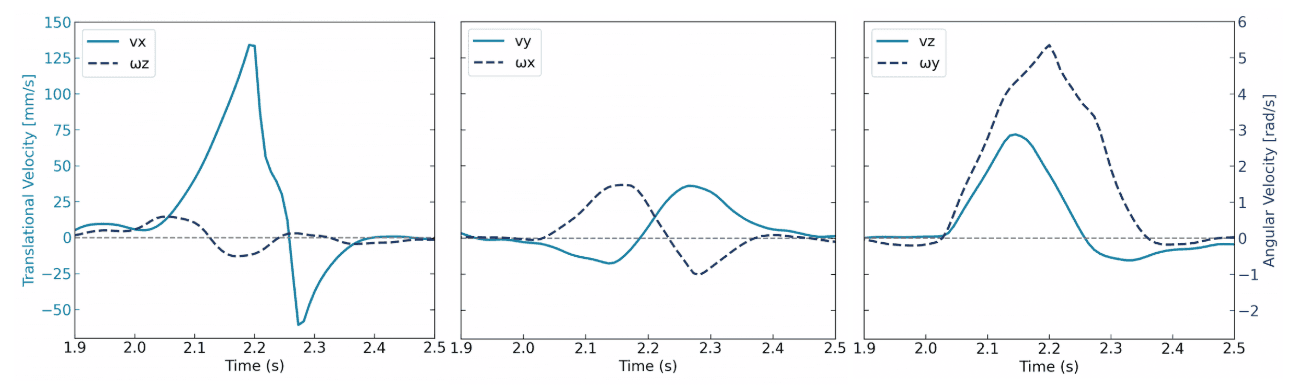

Assuming rigid body motion, we project the absolute positions of the color markers to compute translational and rotational velocities, as shown in Figure 10. Rotation ωy and sliding vx along the toppling direction dominate the motion, but wobbling and sliding in other directions remain non-negligible. The observed wobble arises from asymmetric collision points between adjacent domino blocks.

An additional interactive domino model is provided, offering a more intuitive demonstration of how the absolute positions of six color markers are projected onto rigid frames and subsequently used to compute the motions shown in Figure 10.

Next Step

As tools for quantitatively analyzing full domino motion are developed, precise numerical analysis can be extended to evaluate the stability of wave transmission under three-dimensional rotation. With single-block motion already analyzed, future work will expand to multiple blocks and entire chains.

Additional research directions include studying asymmetric domino chains to account for uneven potential energy, as well as curved or irregularly spaced chains. These variations can be explored in relation to earthquake source models, continuum approximations, and nonlinear dynamics.

A paper focusing on the basic model and classical analysis is currently in preparation.

Acknowledgement

This project originated in the Advanced Physics Lab as a month-long experiment. With the support of Prof. Harlick, Prof. Braverman, Prof. Morris, and lab technicians Larry and Phil, I was able to further pursue the work and explore the topic in greater depth.

I am deeply grateful for their guidance and the opportunity to develop this project, and I am excited about the discoveries and science that lie ahead.